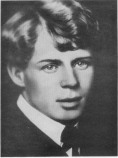

Esenin Sergey Alexandrovich, Russian poet, born October 3, 1895 in the village of Konstantinovo of the Ryazan province. He began writing poetry when he was nine.

Esenin Sergey Alexandrovich, Russian poet, born October 3, 1895 in the village of Konstantinovo of the Ryazan province. He began writing poetry when he was nine.

Following the advice of his teacher, Sergey set off for Moscow to pursue poetry in March of 1913.

In 1914 he married Anna Izryadnova, they had a son in January of 1915. Izryanova described Esenin as arrogant, proud, ambitious and possessive. Soon, he abandoned the family and Moscow for Petrograd, which he saw as a real literary capital.

He was so nervous that he broke out into a sweat when he first met Alexander Blok on March 9, 1915. Blok gave Esenin encouragement and help, calling him "naturally gifted peasant poet". Esenin's first collection of poems, "Radunitsa", was published in February 1916. His fame rose quickly, and he even read his poetry in the presence of the Empress and her daughters, and was awarded with a gold watch and chain. Esenin's sympathies, however, were with the revolutionaries and he warmly greeted both the February and October revolutions. In 1917 Esenin married Zinaida Raikh.

He considered the year of 1919 the best time of his life. He was given control of a bookstore, a publishing concern, and The Stall of Pegasus, a bohemian literary cafe. At this time he formed the Imaginist literary movement. They proclaimed the primacy of "the image per se" and spoke of the image "devouring" meaning. Metaphors were referred to as "minor images". Esenin said:

"Just realize what a great thing Imaginism is! Words have become used up, like old coins, they have lost their primordial poetic power. We cannot create new words. Neologism and trans-sense language are nonsense. But we have found means to revive dead words, expressing them in dazzling poetic images. This is what we, Imaginists, have created. We are the inventors of the new."

In 1918 or 1919, Esenin applied to join the Communist Party, but he was considered too individual and "alien to any and all discipline". Despite his intensely social life, a sense of alienation and loneliness grew in him. In 1921 he notes, "Generally speaking, a lyric poet should not live for long." In November 1921, he met American dancer Isadora Duncan. They married on May 2, 1922, and set off for a tour on Europe and America. Their journey abroad was a disaster for Esenin, who wished his poetry would be well received. In 1923 he returned to Russia, suffering from depression and hallucinations. According to Mariengof, during the journey Esenin became an alcoholic, and his determination to end his life turned manic - he made some attempts. By the end of October, their relationship was over.

In November 1921, he met American dancer Isadora Duncan. They married on May 2, 1922, and set off for a tour on Europe and America. Their journey abroad was a disaster for Esenin, who wished his poetry would be well received. In 1923 he returned to Russia, suffering from depression and hallucinations. According to Mariengof, during the journey Esenin became an alcoholic, and his determination to end his life turned manic - he made some attempts. By the end of October, their relationship was over.

Although his marriage to Duncan was never officially dissolved, he married again to Galina Benislavskaya. His drinking continued. The only time he was sober was when he wrote. But he felt his writing skills waning. He said that he was beginning to write verse, not poetry.

Ah friend, my friend,

How sick I am. Now do I know

Whence came this sickness.

Either the wind whistles

Over the desolate unpeopled field,

Or as September strips copse,

Alcohol strips my brain.

The night is freezing

Still peace at the crossroads.

I am alone at the window,

Expecting neither visitor nor friend.

The whole plain is covered

With soft quick-lime,

And the trees, like riders,

Assembled in our garden.

Somewhere a night bird,

Ill-omened, is sobbing.

The wooden riders

Scatter hoofbeats.

And again the black

Man is sitting in my chair,

He lifts his top hat

And, casual, takes off his cape.

From 'The Black Man'

Translated by Geoffrey Hurley

In the late 1925 Esenin spent some time in a hospital for a nervous breakdown. He had left his wife and went to Leningrad, where he hanged himself in the Hotel d'Angleterre, on December 28, 1925. Before his death, Esenin slashed his wrists and wrote with his own blood his farewell

Goodbye, my friend, goodbye.

My dear, you are in my heart.

Predestined separation

Promises a future meeting.

Goodbye, my friend, without handshake and words,

Do not grieve and sadden your brow,-

In this life there's nothing new in dying.

But nor, of course, is living any newer

The "prodigal son" of Russian poetry, whose self-destructive life style and peasant origins marked his work throughout his relatively short career. Esenin died at the age of 30, leaving a great collection of poetry, but tired of life and poetry. Esenin became a myth and legend, and he is still one of the most beloved poets in Russia.

|

Drowsy feather-grass. Beloved lowlands, This would seem our common dispensation Magical, far-reaching is the moonlight. And when life today is boldly throwing Every night I dream a confrontation Still, though novelty may cramp and crowd me, | |

|

1925 Translated by Peter Tempest | |

|

|||

|

| Copyright © anastasia | anastasia@boxmail.biz |